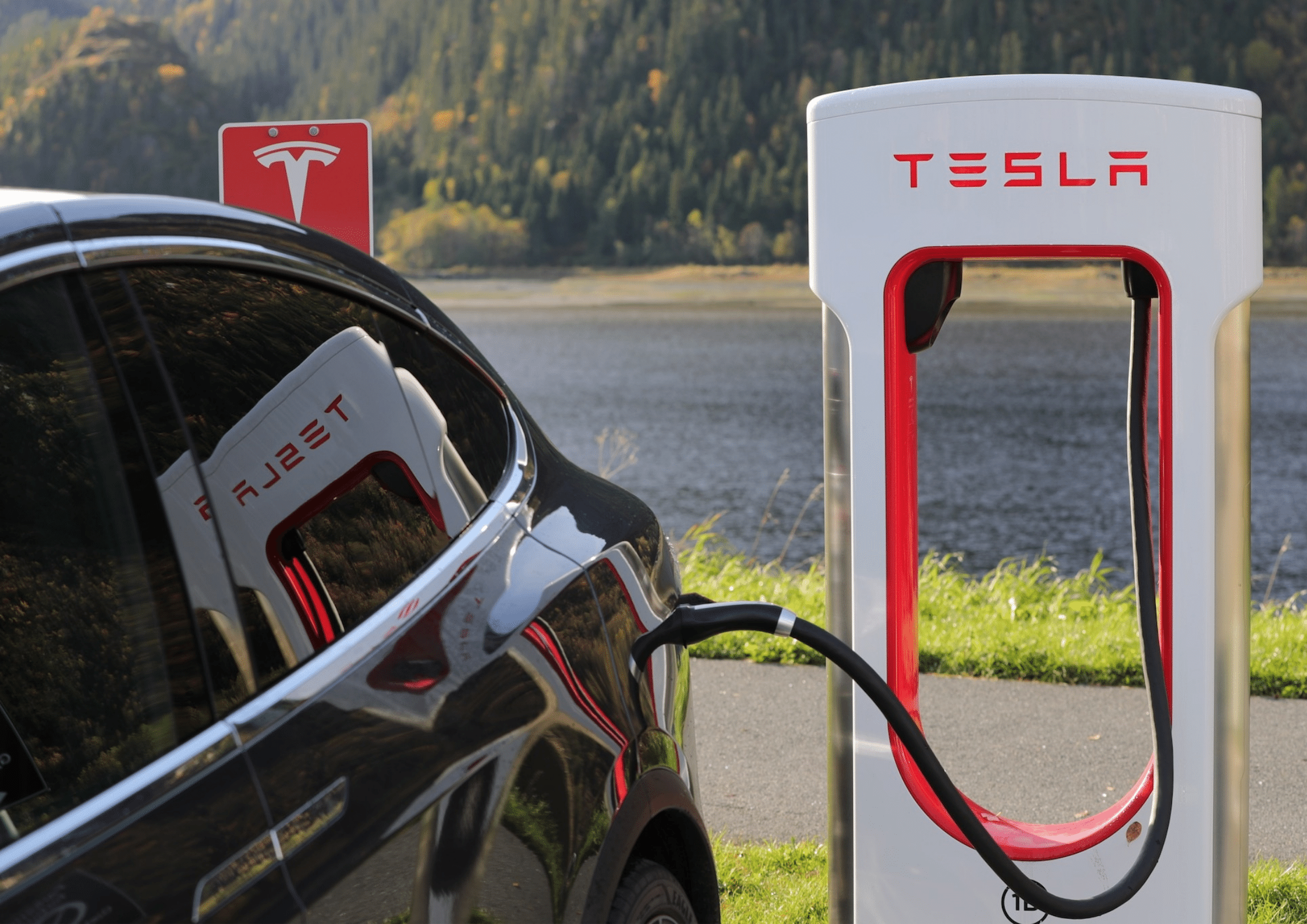

In addition, only some 750,000 Tesla’s ever have been sold in the US, meaning that to have fast charging stations as accessible as gas stations, the company would need to install a $250,000 Supercharging station for every 23 cars it had on the road. Quite obviously, that’s not feasible, as the stations would never break even with such infrequent use, and that’s the exact problem. You need the infrastructure to sell the cars, but you can’t build the infrastructure until you sell the cars. It is the classic chicken and the egg problem. There might, however, be a solution.

According to federal government data, there are some 3,845 non-Tesla DC fast-chargers in the US—the vast majority of which could charge a Model 3 within an hour… assuming it could connect. Just as there was a format war in the 1880s between DC and AC power, there is now a war of charging standards. Take the example of Salina, Kansas—a small city off of Interstate 70, which most people only visit to refuel or, in this case, recharge. This Supercharger uses Tesla’s proprietary plug, this Electrify America station uses CCS, and CHAdeMO plugs, and this hotel’s charger uses a J-1772 plug. There are four different plug types in one small city.

Now, a Tesla could use the Tesla charger and the J-1772 charger with an included adapter, but it could only use the CHAdeMO charger with a speed-limited $540 adapter, and it couldn’t use the CCS charger at all—as there’s no adapter for that plug-type. Meanwhile, a Chevy Volt EV wouldn’t be able to use the Tesla or CHAdeMO chargers at all as there are no adapters available for either to its CCS plug.

This means that to accommodate every vehicle type, DC fast chargers need to have three different plug types, which, overwhelmingly, they just don’t. Especially along Interstate highways, there are the Tesla stations, and there are combo CHAdeMO and CCS stations. Just like Edison and Westinghouse delayed more widespread adoption of electric power by competing against each other in the same areas with their different, incompatible AC and DC standards, different stakeholders in the electric vehicle market are competing against each other in the US to create redundant, largely incompatible networks.

But that’s not happening everywhere. You see, in Europe, CCS is the standard. The European Union has a directive which means that many member states, by law, require that public DC fast chargers include a CCS plug. Therefore, in the EU and neighboring countries like the UK, Norway, and Switzerland, CCS is now the de facto or de jure charging standard. That forced Tesla’s hand to the point that in 2018, it retrofitted all its existing Superchargers with CCS plugs, switched its Model 3’s to CCS, and released an adapter allowing its other models to use CCS chargers.

All told, this means that pretty much any car in Europe can use pretty much any DC fast charger. That, combined with Europe’s higher population density, has helped ensure that the density and coverage of DC fast chargers are much greater than in the US, despite the fact that EV ownership per capita is actually higher in the US than Europe as a whole—although certain European countries far eclipse the US’ rate. Europe is almost identical in size to the US, it has a very similar number of electric cars overall, but it has double the number of DC-fast charging stations. In Germany, the furthest you can seemingly get from a DC-fast charger is here, in Winterberry.

From this small ski-town, the nearest fast charger is about 30 miles or 50 kilometers away in Marburg. Meanwhile, in the US, if you wanted to drive directly from Dallas to Denver, two major cities, using a base-model Tesla Model 3, you just couldn’t. There’s a 226 mile or 363-kilometre stretch with no DC fast charger between Amarillo, Texas and Trinidad, Colorado, which, given the elevation gain, the car would not make. While Tesla is plugging this gap soon with a new charger in Clayton, New Mexico, that won’t solve the problem for every single other EV on the market since the charging systems are not compatible. Simply put, mass-market consumers are not going to buy cars that can’t drive from Dallas to Denver.

What Europe has that the US does not is coordinated government plans. Germany’s federal government, for example, builds its own charging stations, in addition to offering strong incentives for private companies to do so as well. Meanwhile, the federal government in the US has done very little to incentivize fast-charger construction, and certainly does not have a network of its own. Certain states, such as Oklahoma or Colorado, do have strong, coordinated government programs to build fast charging infrastructure, meaning even shorter-range EVs can drive essentially anywhere in each state without encountering a fast-charger gap, but the problem is that EV drivers from Colorado or Oklahoma will eventually want to drive through Kansas, or Nebraska, or Wyoming, or other states that do not have a coordinated plan.

The US Federal Government clearly wants people to buy EVs, because it offers hefty tax credits to those who do so, but people are not going to buy EVs without the charging infrastructure to support it. EVs are comparable in cost to internal combustion cars, their range is about what consumers demand, but what’s lagging behind is that charging infrastructure. This isn’t even an exclusively American problem. In Australia, one can’t drive from Perth to Sydney—the country’s forth and first most populous cities—in an EV, due to a massive charging gap, while in Russia, despite similar incentives for EV purchases, there are a total of 24 DC-fast chargers in the entire country.

Of course, some will always debate whether governments should be incentivizing electric vehicles at all, but regardless of that, they are—it’s tough to find a developed country that does not have some tax or other monetary incentive for EV ownership. The point is that they’re incentivizing the wrong way. EVs are very, very close to reaching the tipping-point criteria for everything but charging. Cost is not standing in the way, technology is not standing in the way, infrastructure is, so governments are putting the cart before the horse.

Individual companies cannot reach the required scale, and even if they did, as the format war in the US proves, it probably wouldn’t be the kind of scale that the mass-market consumer demands. Individual car companies can deal with making individual electric vehicles attractive to consumers, the government doesn’t need to worry about that, but infrastructure—that’s the government’s job. Governments run or regulate roads, and bridges, and tunnels, and sidewalks, railways, airports, electric grids, dams, sewers, water supply networks, and even fuel supply systems, because they are infrastructure, and infrastructure is essential, so the only question is: why not charging?

So, as you might have guessed by now, I own an electric vehicle, so I took it to my local Tesla Supercharger to make a companion video to this where I give a super detailed, super nerdy explanation of exactly how a Supercharger works from a technical perspective.